A blog about a life lived in literature and a career in publishing, with occasional musings and rants.

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

Science fiction is more than a Spock costume

No, no, the Point of this blog post is that I like dystopian and post-apocalyptic fiction, as well as a difficult one to define: fiction about the city - not just set in it or a travel guide or a map, but wherein the amorphous spirit of the city is a character - and this is mostly labelled science fiction so that it doesn't have to live in the same hovel that Kanye (who?) will one day inhabit.

The genres of science fiction and fantasy do not have fans, they have cults. Compare the fans of Legally Blonde with those of Star Trek. Unless things have changed in the last 6,5 minutes since I checked my RSS feed, blondes whose peroxide has burnt its brand logo in their brains and who trip over crucial evidence in a trial and claim to represent women's lib, do not host massive conventions that even the producers of Legally Blonde and Twilight now attend.

I am not a cult fan. Of anything much, including life. (Nor am I blonde, nor do I scream (I tried once and all I got was a scraping caw) and the fool who tries to rescue me will get a weapon from my weapons belt lodged in his eye socket.) Except books. I will go to the grave insisting that The People's Act of Love (yes, that book, and shut it) is the best book written in the last two centuries and I would proudly host a convention in the topic, although I wouldn't dress up as one of the characters because they sound smelly.

Woman on the Edge of Time was a surprisingly powerful novel - surprisingly because I had never heard of it before a friend recommended it. (I could go on a rant about how literary literature written by women (nevermind anything that has a socialist flavour) and science fiction are herded into their own hovels. But I won't.) It is about a woman whose one alter ego is in a psychiatric hospital (the kind where they throw away the key) and the other finds herself in an utopia of the future.

This sounds like a Bruce Willis movie, which isn't a bad thing because 12 Monkeys is still sitting with me and I enjoyed Looper. Now here is a more appropriate place for aforementioned rant. The novel has distinct feminist and socialist flavours. It was written in the 70s, when the world (read America) was more idealistic in that it believed that the ideal could be won if you fought for it. (Now their children are doing the same; search Anonymous + hackers and OccupyChicago/SanFrancisco etc.)

How does that make you feel? Are you less or more likely to read the novel than when I initially recommended? Why? I'll admit that if I had known, I would have hesitated to pick it up now. It sounds... heavy, I would have said. I being the person with Ulysses, a book that is undecipherable according to those in the know i.e. who have finished it, on my dresser and Murakami's 1Q84 on the bookshelf. I being the person who reveres The Road as cruel, beautiful and illuminating.

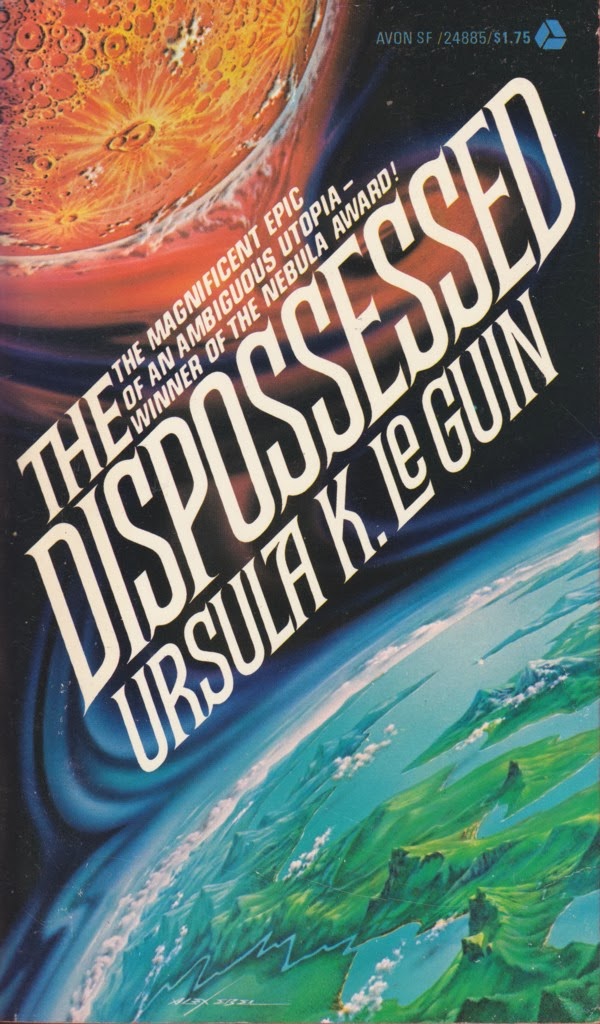

This was not what I had intended to blog about. I was going to follow up with The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin. But this is another heavy novel, full of feminism and socialism and human rights, and I am too tired to lift it, so I guess you're too tired to read it. If you're still there. You might be reading through the troves of articles about Anonymous - now there's a real life story designed to extract the idealist in you. (Ask Kanye to sort it out.)

I do like the list of things I like above. I enjoy novels that pick me up out of my comfort zone so that I can view the world around me, without feeling like none of this chaos can be contained or sanitised. These novels outline my own ideals, so that I can scratch up the edges in the real world. So I guess I have tricked myself and returned to the original tired premise. It's tired in part because of the labels we have stuck on it. Science fiction is more than a Spock costume. That is the type of fiction I like.

Sunday, December 29, 2013

Doris Lessing, 1919-2013

A dull yellow (impersonating gold) trade paperback, in library-grade plastic and accompanying Dewy-decimal-system label on the spine. This was when I first met Ms Doris Lessing. (Disclaimer: it was not The Grass is Singing, because a BA degree is an overdose in colonial and post-colonial fiction. Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez is tainted by my grand nemesis The Heart of Darkness - Mr Achebe, while I'm with you about the layers upon layers - no, actually, just one deep layer - of racism, it is also one deeper layer of boring.)

The Golden Notebook. My first handshake with Ms Lessing. Not literally. Read above, please. Read the title. Focus!

I was about 20, in my gap year between one degree and the next, naively contemplating the theme of my adult life (naively because, as you know, dear reader, that theme snaps at your heels, accuses you, does back flips and takes your spot on the couch endlessly - right? Or is this just me?).

In brief (this book is anything but brief), the novel is comprised of five, different coloured (not literally, fool) notebooks and a binding story set in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. The protagonist is a middle-aged woman named Anna Wulf, living in London. (For those who know Ms Lessing's own story or have the power to Google, the plot(s) resonate.)

The book was written in 1962. We could ascribe the politics of the novel to the time - and this probably didn't hurt sales - but these themes could be traced back to the novel of the singing grass and Ms Lessing's liberal but tempered temperament. The themes (of both novels) include feminism and socialism (loaded terms, but that's why there's Wikipedia (again, encyclopaedia is spelt with an 'a', open source dorks).

Even as a teenager, perhaps even a tot, I have gravitated toward these liberal movements - I shudder as I type 'liberal' - literature tells me liberals are too impassioned to be rational, misguided and unfocused, appealing to human nature rather than the greed, envy, lust and basic selfishness that natural selection rewards. Trust me, I went to a politicised university and have seen two riots. Wait, now I'm a voyeuristic, liberalesque pseudo-intellectual. Still, call me a liberal and I will... moderate your comment. You.

The novel stalks the measure of the terms - from the perspective of the times, obviously; I later learnt more about the revolutions before and after (and no I'm not talking about #Occupy-a-park) - setting my principles in some sort of shape, like water in an ice block (just way more haphazard). Feminism was the one that immediately appealed to me. Given that a comment about women drivers is still enough to incite me to violence - or wait, my favourite "She's a smart cookie." Do I look like a gingerbread woman?

Today, when I think about the novel, some shadow of the experience of reading projects on the back of my head. Of sitting on a forest-green couch in a room painted yellow. Of the view from a kitchen window of a London street. The aura of importance that being involved in grand ideas provokes. Of a mother and her children, with the realisation that a child is a separate being to her. Of gritted teeth as a man, of common mind, tells a woman what feminism means.

None of these are necessarily written in the book - but they are what I see when when I think of it. They are a set of first dates with the world around ideas I thought were mine. A world which the mass media do not quite grasp.

I had ordered two of her novels online and they were delivered the day before she passed: Mara and Dann and The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog. Predictably (for me) they are dystopian novels, predictably (for her) written to explore political and social issues. Reading them feels like a ritual honouring her and her effect on me. What else will she teach me? What other ideas will she help me shape?

Doris Lessing was one of the greats, unassuming but influential. This post is my tribute to her and acknowledgement of her influence on me. And an assuaging of my guilt. I confess I have undervalued the author over the last few years. Read my archives and she doesn't appear, except as a passing reference. As often happens, it has taken her death and the reeling of my world to make me appreciate Doris Lessing and The Golden Notebook.

Footnote: Stay posted (har!) for reviews of Mara and Dann and its sequel. I will try to keep the soppy to a minimum.

Saturday, October 20, 2012

A brief (incomplete) history of revolution

What do The Dispossessed by Ursula le Guin, the Communist Manifesto and the recent Wall Street sit-ins have in common? (Actually, that should be obvious, and if not, read one or both and you'll get it.) I was reading The Dispossessed and the Communist Manifesto (I always read one fiction and one non-fiction book at the same time) at the same time as the sit-ins began.

It seemed as though history (and literature) was repeating itself. I was born in the early eighties and grew up in the nineties, when a popular culture rebellion gave way to an intellectual cynicism. I tend to view any group gathering with caution (and perhaps some degree of apathy), because the efforts of decades of Russian revolution, the hippies' campaigns of non-violence (and socialist-inspired and Epicurean free love) and the more sinister rebellions of punk culture and similar obnoxious groups, came to nothing. They all collapsed into their own centres and dispersed.

I've also read enough dystopian novels to know better.

The weak point of any such collective action is that eventually it matures into sets of rules and hierarchies - becomes a system. Those rules and hierarchies become ends in themselves, and all those naive (also hopeful) values are absorbed and become means to those ends. The followers become disillusioned and are not replaced by enough new recruits to keep the movement going. If it doesn't develop, it becomes static and eventually peters out.

The version of the Communist Manifesto I was reading was The Communist Manifesto and Other Revolutionary Writings, which presents the writings of influential philosophers in chronological order, so that you can trace the seeds of socialism. (This was where I met Bakunin, who dipped me into anarchism.) The speeches of the leaders (and followers, who often take up their phrases as mottos, without always knowing what they mean) were less coherent paraphrases of these writings! Did they know? Were they philosophy drop-outs who didn't have the patience to delve deeper? Or did they intentionally use and abuse these phrases to hook followers and confuse their opponents?

This last is a strategy recommended by Leon Trotsky. But if these political philosophers had delved deeper, they would have found that this is Stage 1 of Trotsky's map for rebellion. The second is to link those mottos to concrete action. Even if those actions are extreme. Because they're linked to what has become a value system, the actions seem necessary. Voile, you've accomplished a coup without much (only necessary?) violence and so swiftly that the collective has no time to question it until they're already implicated.What does The Dispossessed have to do with this? Hey, I'm not giving you all the answers! Read it and see what you think. And, while you're at it, try Woman on the Edge of Time by Madge Piercy.

.jpg)